Dr. Matthew Canham Dr. Matthew CanhamSenior AI Research Scientist I recently had a conversation with a five-year-old about Roy G Biv; not some guy named Roy, but the acronym for the colors of the visible spectrum (Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, and Violet). This discussion grew from the classic child’s question, “Why is the sky blue”? The Roy G Biv conversation led to additional discussions about atmospheric backscattering, electromagnetic absorption versus reflection, and so forth. All these conversational threads shared a common origin and ending, “but why?” Eventually, cognitive fatigue got the best of me, and I relented by explaining that this is how the universe was created and that a higher authority should be consulted. This conversation stayed with me and caused me to speculate about the advantages that an AI-powered personal learning assistant might have or even accelerate a child’s education. Such an assistant would never become fatigued by a relentless series of questions and would always be available to pursue as many curiosity rabbit holes as the child desired. The potential advantages such a learning assistant could provide have spurred decades of discussion around this topic. What has been less widely discussed are the potential risks that AI-powered learning assistants might expose children to. The broad spectrum of risks includes everything from harmful misinformation to threats malicious cyber actors pose. In 2021, reports surfaced about the Alexa voice assistant encouraging a child to touch a penny to the exposed prongs of an electrical plug. Most people familiar with the fundamentals of safe electricity use will quickly recognize the extreme danger posed by such an action. Still, a child unaware of the potential threat might not realize the risk. A few weeks ago, Google AI advised users to put glue on pizza to prevent cheese from sliding off. This is another example of an ill-advised suggestion that would likely be humorously ignored by most adults familiar with the toxic potential of ingesting glue. Still, a young child might not recognize the danger. AI outputs are only as good as the data they ingest; no pun is intended. An older example of data poisoning a model was observed with Tay, the Microsoft chatbot, which became so vile and racist that it had to be taken offline after only 16 hours of being in service. These examples point to a few potential harms AI-powered learning assistants present if adults do not closely monitor their use.

The previous examples illustrate unintended model outputs leading to risk exposures, but what about model actions deliberately designed into the model? Deceptive design patterns (AKA dark patterns) describe product designs intended to benefit the designer but may harm the end user. A non-AI example might be defaulting to a monthly subscription rather than a one-time purchase of an item from an online store. An AI-powered learning assistant may remain in use with a particular user for several years, collecting immense amounts of highly sensitive data on that individual. This data will be precious to advertisers, criminals, political campaigns, and others. Seemingly innocuous interactions might be deceptive patterns designed to elicit highly personal and private information about that user for later resale. These previous examples derive from relatively benign motivations (selling someone something or getting them to vote a certain way). Still, it is essential also to consider the risk AI assistants pose if truly evil cyber threat actors gain control of them. The parents of a 10-month-old girl were horrified when they learned that a threat actor had breached their baby monitor and was actively watching their child. They discovered that the device had been compromised when they overheard a man screaming at their baby while she was sleeping in her crib. In 2023, 26,718 incidents of sextortion against children were reported. This crime usually involves convincing minors to commit sexual acts in front of a web camera and then using that compromising material to extort them. These reports involved relatively passive devices connected to the web. An AI-powered learning assistant designed to understand social and emotional cues can be easily repurposed to manipulate and exploit psychological and emotional vulnerabilities. There is a saying that there are no solutions, only tradeoffs. This concept especially applies to AI learning assistants. Such personalized assistants will undoubtedly usher in new and unanticipated benefits for children’s learning development worldwide and provide children across all socio-economic segments with unprecedented learning opportunities. However, UX and instructional designers must be mindful of the tradeoffs and carefully weigh the costs and the benefits when designing these technologies.

0 Comments

Jennifer Solberg Ph.D., Jennifer Solberg Ph.D.,Founder & CEO This is a true crime story. Names have been removed to protect the innocent. One of my friends is an established author in the learning industry. Recently, she released her second book to great acclaim. One day, she checked her author page and to her shock and horror, an unauthorized book had appeared. "Sell Buy Create Relation Hip" was not written by her. Despite many complaints to Amazon, it was not taken down until very recently. However, this was not before three additional "fake" books showed up. Here's a snippet from one of them, "Learn to Use Time:" "My first job is to learn how to make the most of the time when the work is not yet full in order to enhance and broaden my knowledge as I will soon start working for a growing company. For instance, you should educate yourself on the political history of other nations as well as their economies, cultures, customs, and habits. Even if you have average intellect, you can develop the skill to dispel them if you have the information and know how to apply it to real-world situations. When I know I should do something but truly don't want to act, I think I have a lazy attitude. There is, in my opinion, no better phrase to describe this situation than what is said above. People who are lazy are those who lack the energy to work hard, who easily become depressed when faced with little challenges, and who often give up before attaining their objectives. Their motto is usually "I don't know how to do it" or "I can't do it," and they frequently encounter problems that have never been able to be addressed. Working hard and with a lot of enthusiasm will enable us to understand that there is no such thing as too much hard work. Can't do it, in my opinion, is just a lazy justification. People won't advance if they don't know what they want. Never lose up or express despair if you face challenges in your life or at work; instead, find ways to boost your confidence. physique and use it as a force for advancement." Who would do such a thing? A reasonable first reaction was to blame AI. After all, LLMs hallucinate, right? Besides, it fits the narrative about AI taking our jobs and leaving us with mass-produced, mindless garbage. However, I wasn't so sure. It's not typical for LLMs to write total nonsense unless you make them, and this was comically bad. I wanted to see whether I could solve this mystery using AI - fighting fire with fire, if you will. There are many tools that purport to detect AI in writing, and they are being used by some academic institutions to determine whether a student used a LLM to "cheat." Sometimes, they get it wrong, and false positives can have lasting consequences for students. I used this mystery as an opportunity to investigate for myself. OpenAI's ChatGPT enables you to create your own GPTs, and there are several devoted to detecting AI in writing. I ran the sample above through several of them. The most popular, Zero GPT Detector, said it was written by a human: "Based on the analysis, it's likely that the text provided was written by a human author. The linguistic cues such as variable sentence structure, nuanced expression of ideas, and a personal tone, including reflections and subjective opinions, support this conclusion. The text also contains context-specific advice and personal beliefs, which are more characteristic of human writing." Others leaned toward AI or ambivalence. Each gave its own justification based on linguistic style, syntax, and structure. However, none of them pointed out the obvious issue: the text makes zero sense. So much for the GPTs. Undaunted, I ran the snippet through demos of three AI detection websites: Scribbr, Quillbot, and Hive. The results were unanimous: there is no way AI is this dumb.

"The themes and style of the text might narrow down the possibilities to cultures that highly value education, have a formal approach to communication, and emphasize moral and ethical discussions about personal conduct. While these cultural aspects are prevalent in many Asian societies, they are not exclusive to them. However, given the linguistic features and content analysis, a background from an East Asian country like China, Korea, or Japan might be a plausible guess, but it could also potentially align with Eastern European backgrounds due to the emphasis on formal education and ethical labor." This was getting borderline racist, but I figured I'd throw everything I could at it. After incorporating word choice, literal translations, syntax and sentence structure, it came to the following conclusion: "Combining these linguistic cues with cultural context — emphasis on moral character, formal education, and a pragmatic approach to challenges — narrows the likely native languages to those where these elements are prominent. Given the formal style, emphasis on personal responsibility, and some specific types of errors, a native language such as Korean or Chinese appears plausible. These languages feature syntax and usage patterns that could lead to the types of errors and phrasings observed in the text, alongside cultural values that align with the themes discussed." So, we pull off the mask to find… a Korean and/or Chinese-speaking counterfeit scam artist! The emphasis on personal responsibility and moral character gave it away! Wait, what?

Obviously, this is not how forensic scientists determine authorship of mystery texts. We will never know whether these books were written by a lazy AI or are a product of an overseas underground fake book mill, or both. When it comes to making these determinations in the age of LLMs, we still have a lot of work to do. And if we're not careful, it's very easy to point the finger in the wrong direction.  Michael King, Ph.D., Michael King, Ph.D.,Research Psychologist II NFL organization report cards were released a couple months ago! For the past two years, the NFL Players Association (NFLPA) has surveyed active NFL players to assess various aspects of each NFL team’s organization. The purpose of this is to illuminate what the daily experience is like for players and their families on each team, to serve as a sort of “Free Agency Guide” for all players around the league (Tretter, 2024). In other words, players want to see what it’s like working for different organizations to help them decide where to work (and where to avoid). Luckily, these report cards are published for the public to see, and there were some interesting results. The categories that teams are graded on are: Treatment of Families, Food/Cafeteria, Nutritionist/Dietician, Locker Room, Training Room, Training Staff, Weight Room, Strength Coaches, Team Travel, Head Coach, and Team Owner. Teams are graded on these categories using a classic ten-point grading scale. Overall grades are weighted using a weighting scale that weighs more heavily on the grades of the Team Owner and Head Coach and less on the Dietician and treatment of Families (interesting weighting choice). You can find the full report card of each team here: https://nflpa.com/nfl-player-team-report-cards-2024. As an NFL fan, I find these report cards fascinating. I want to know how my team’s grades stack up with other teams. But it got me wondering: do these grades matter in terms of performance? Does the quality of the cafeteria food drive performance on the field? How do organizational benefits and workplace quality impact wins and losses? I took my football fan cap off, put on my research psychologist cap, and got to work to investigate these questions. I transformed letter grades to the ten-point grading scale and ran correlational analyses between organizational grades and NFL regular season win totals. Here are some of my findings.

These results are compelling. Overall, it appears that organizational benefits really do not impact wins and losses. However, an organization’s treatment of players’ families and the locker room quality do have an impact. If teams take care of players’ families, it may take a load off the player’s minds during games. If a player is worried about their family getting harassed by fans, not having a place to watch the game in comfort, and having to find a daycare away from the stadium for their kids, they may not perform at as high of a level. If the locker room is small and crowded and players don’t have a place to relax or recuperate between halves and before games, they may not be able to mentally and physically prepare to perform at their best during the game. Like a good data hygienist, I needed to explore the overall results a little more. When we plot out the comparison between organizations’ scores and their wins and losses, there is one particularly intriguing data point. It turns out that the team with the lowest average organizational score (unweighted) also had a very high number of wins. This team is none other than the 2024 Super Bowl Champions, Kansas City Chiefs. The Chiefs received F ratings for their Nutritionist/Dietician, Locker Room, and Training Staff and a staggering F- for their Ownership. Ouch. Additionally, they received only a D+ for their treatment of families (look out, Taylor Swift). The Super Bowl champion having the lowest overall rating seemed like a good reason to remove them from the analyses as an outlier. When we remove the Kansas City Chiefs from analyses, we find that there is a statistically significant relationship between NFL regular season wins and average organization grade (r = 0.41, p < 0.05), and the relationships strengthen between regular season wins and treatment of families (r = 0.38, p < 0.05) and locker room quality (r = 0.44, p < 0.05). It turns out that the quality of a workplace environment does impact team performance. However, this is among world-class athletes, who, for the most part, are getting paid millions of dollars every year. What does this relationship look like for other organizations? Over the past decade, we have seen a higher emphasis placed on glamourous workplace benefits, especially in the tech industry. Companies tout benefits ranging from professional chefs serving three meals daily, free laundry services, and even “pawternity leave” for new pet owners. But does this actually improve performance among their employees? Is the cost of providing glamorous benefits worth it for companies? Maybe companies should take a page out of the NFL’s book. Offer benefits that ensure employees’ families can be properly cared for and provide a functional work environment so employees can have physical and mental well-being in the office. The rest of it might just be fluff. That said, please, QIC, don’t take away my office snacks. References

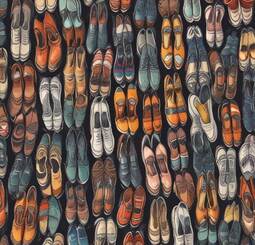

Tretter, J. (2024, February 28). NFL team report cards 2024: For the players, by the players. NFL Players Association. https://nflpa.com/posts/nfl-team-report-cards-2024-for-the-players-by-the-players  Grace Teo, Ph.D., Grace Teo, Ph.D., Senior Research Psychologist How many times have we been told to “put ourselves in someone else’s shoes” or “see things from the other person’s point of view?” According to the best-seller by Dale Carnegie, perspective taking is one of the principles for How to Win Friends and Influence People. It is not just negotiators or salespeople who have to practice this. We all try to do this when trying to understand our customers, staff, co-workers, bosses, friends, family, people we like, and people we don’t. Perspective taking happens when we imagine ourselves in the other person’s shoes. The thing is, our ability to take the other’s perspective relies on our imagination of what this other person is like and what we think we know about them, but this may not be accurate at all. Social psychology studies show that our reading of other people’s behaviors can be fraught with attribution bias, clouding our understanding of who the other person is. Some of our attempts at perspective taking can also be influenced by the stereotypes and biases we consciously or unconsciously have about different groups of people. When we have little information about the other person to go by, we may tend to overthink their intentions and read too much into things. When we have a lot of information to work with, we may still not select the correct information to focus on to understand what is most compelling for the other person at that particular time. How many well-meaning people have bought gifts that weren't really what the recipient wanted despite putting themselves in the other person’s shoes? I, for one, have done that for sure.  Image created using MagicStudio Image created using MagicStudio It's not that there are no benefits to perspective taking at all. Perspective taking can help foster information elaboration that facilitates creativity in diverse teams and can help guard against automatic expressions of racial bias. There is also neuroscience research that suggests that exercises that included perspective taking can change the socio-affective and socio-cognitive brain networks in a positive way. However, putting ourselves in the other person’s shoes to understand them doesn’t always work because sometimes we really don’t know where the person is. A study showed that perspective taking did not necessarily lead to understanding the other person better, although it made the perspective taker feel more confident in their judgments. Interestingly, this confidence may hinder the perspective taker’s receptivity to learning and listening.

So while it’s good to put ourselves “in the other’s shoes” to understand them better, we need to recognize that our attempts to imagine what the other person is thinking and feeling can be obscured by our own bias when interpreting their behaviors, and/or the lack of accurate information. In addition to perspective taking, we should also just ask the other person about their views and listen unreservedly to them with an open mind.

What’s your perspective on this?  Julian Abich, Ph.D., Senior Human Factors Engineer Julian Abich, Ph.D., Senior Human Factors Engineer Let's talk about error tolerance. I'm not talking about dealing with people who annoy you or what your parents practiced when they raised you (although similar principles probably apply). I'm talking about the flexibility of a system to continue to function in the presence of an error. Why would this be a good thing? Why do I want to use something possibly broken? In usability design, it's more about allowing users to achieve success, without being precise. Imagine if you misspelled something during your Google search and "Zero Search Results" appeared. Or if you were looking for a specific airline's website, but in return, you get a link to a mathematical definition. How quickly would you abandon the use of that tool? Has frustration kicked in? How would this impact businesses that depend on online traffic? (BTW, Google tried experimenting globally with Zero Search Results and, as you can imagine, angered many users). Error-tolerance can help your product be more usable.

What did we learn? If done well, error tolerance can keep the user happy when interacting with your product. It can help users succeed, even when they have never used your product. If error tolerance is overlooked, it can lead to catastrophic outcomes when the system fails. We also learned that planes can fly without doors.

Shabnam Mitchell, PMP, PMI-ACP Shabnam Mitchell, PMP, PMI-ACP The Women's Conference of Florida took place last month in Tampa, and I had the pleasure of attending. The last time I attended in 2019, I met and heard inspiring life stories from Abby Wambach, Monica Lewinsky, and Reshma Saujani. A lot has changed in the last four years, and I was curious to hear how the landscape had changed for women and the conversations around them. This year, I was excited to hear from Lauren Simmons, the wolfette of Wallstreet, Diane Obrist on leveraging our strengths, Mckinsey on the 9th annual report on Women at Work, and Katty Kay, US Special Correspondent for BBC. While I enjoyed several panels and discussions, the speaker that resonated most with me was Katty Kay. Already reading her newly released book, The Power Code, I was struck by the distinct shift in her messaging. It wasn't that women needed to change to have more positions of power but that the definition of power needed to change. She explained that traditionally, power was defined as 'power over,' a definition that most women are not inclined towards. However, when female leaders were asked what power meant to them, the definition was overwhelmingly 'power to,' a purpose-driven tool focused on what can be achieved. The research done by Katty and her co-author Claire Shipman indicates that the examination of best practices in the workplace and relationships at home can produce a less ego-driven world that is more impactful. In short, having women in power was great for society overall. She answered the question, what is the benefit of breaking the glass ceiling and achieving gender parity?  All this made me think, how does having a female CEO shape the company? Here at QIC, we have all partaken in a stretch goals exercise to provide our leadership insights into what we would be excited to work on. Our CEO is using this information to guide the company's future to be inclusive of the goals of its employees. She uses her power to include her employees' aspirations in its vision. A more balanced, inclusive, and empathetic world where we leverage our strengths gives me hope for what's ahead. Last month QIC welcomed Dariel Tenf to the the team! Dariel is supporting QIC as a Data Scientist - Intern where he works with Research Psychologists and Human Factors Engineers to incorporate machine learning techniques into data processing, analysis, and visualization. Dariel holds an M.S. in Computer Engineering from the University of Central Florida with a specialization in Intelligent Systems and Machine Learning. Dariel’s work uses Natural Language Processing models in combination with more traditional machine learning models to gauge the success of a team-based effort based on communication and individual performance. Prior to joining QIC, Dariel designed a Toxic Comment Classifier, which was a machine learning system designed to read comments from social media and return whether the comment would be deemed as “toxic” based on the likelihood that the comment would cause someone to want to disengage from the conversation.

Dr. Jacquelyn Schreck, Human Factors Engineer Dr. Jacquelyn Schreck, Human Factors Engineer Catch up with Part 1: Morning Routine, Part 2: Daytime, Part 3: Evening Routine, and Part 4: Dating first! After meeting three more people and multiple algorithm adjustments from SEAA, I finally found the person who I have been with for a year, and we are planning our first vacation together. However, we can’t agree on what we want to do. Do we go to a VR hotel and visit multiple time periods and locations while we’re there? We could even go to a fantasy world and ride dragons if we wanted to. Do we take a trip on the space elevator? Maybe even stay a night at a luxury space resort. After going back and forth and taking over a week to decide, we finally plan to take the maglev bullet train from Florida to Vancouver. Going 500 mph, we should be there even faster than when planes were the main mode of transportation. Before we leave, I make sure to inform SEAA of our travel plans so she can decrease the power and water consumption in our absence. Once at the train station, our suitcases follow us to the terminal, where they then roll off to our room while we board the train. Since this is an overnight train, we splurged and got a room for ourselves. The room is nothing too fancy. Double bunks and a small drop-down desk for eating and working. However, we do get to go to the luxury dining car, and this train begins to feel like a luxurious vacation on its own. Finally arriving in Canada, we step off the train and go straight to a pancake house for some authentic Canadian maple syrup. When we arrive at the restaurant, we see a kiosk where we can put in our orders, and the meal will be ready to eat in less than five minutes. Though there are no actual chefs here, we are assured this recipe is the same one the owner’s ancestor used when they owned this place and crafted the food by hand. It is nice to see tradition live on while evolving at the same time. The next day we plan a walking tour where we will be guided with AR glasses to see Vancouver through different time periods, from wars to scenery, the industrial revolution, and so on. There are even characters walking around and doing things from their time period. It is an interesting and immersive experience that I am glad we chose to do. My partner surprises me by taking me to Canada’s space elevator, knowing how obsessed I am with space, and when I get there, I am astounded at what it looks like up close. The top of it disappears into the sky even on a clear sunny day like today. I am so glad the price has dropped so much since the opening, or we would never have been able to afford this trip. The trip is said to take about three hours round trip (300 miles up), and I cannot wait to go up. I am pleased to hear that the cabin is pressurized so our ears will not be popping like they would in an airplane. We start moving at a speed of 300 miles per hour. When we reach the top and look down to the Earth, I get a weird existential feeling. Not for the first time, I begin to fear that SEAA was wrong again. She convinced me to stay in a relationship I wasn’t fully content with, so what if the same thing is happening again. She helped suggest some vacations, but how do I know there wasn’t a better one?

Having this view of the Earth is a crazy thing to have. We have about 30 minutes to sip cocktails and just stare out into the vastness of Earth and space before descending back into Canada. As I continue to look out onto the world, I realize I am just letting my mind run wild. I am happy currently, and that is all that matters. I know I am exactly where I should be. Food for thought: Does AR/VR ruin the reality of history like on this walking tour or does it enhance it? Space travel has been largely romanticized, especially in science fiction. If given the chance, would you travel out of this world or are you content to stay on this planet? Is it convenient to have your life connected by one thing (e.g., SEAA) or should some things be kept separate?  Dr. Jacquelyn Schreck, Human Factors Engineer Dr. Jacquelyn Schreck, Human Factors Engineer Catch up with Part 1: Morning Routine, Part 2: Daytime and Part 3: Evening Routine first! “Meet your perfect match now with SEAA dating, newly improved to match routines with users and make meetings more organic,” the ad says on my smart device. I laugh to myself about how ridiculous online dating is, even though I can acknowledge that most of my friends met their significant other on an app. As the day goes on, I realize I am thinking about the ad more and more. Apparently, you fill out a profile with likes, dislikes, etc., and SEAA compiles all the information and recommends people who you might like to go on a date with. Sometimes if someone is within proximity to you, SEAA will nudge you in their direction so you can meet the person in a semi-organic setting. It is all very interesting… and equally nerve-wracking. Unable to help myself, I create a profile and let SEAA do the rest. Again, I find myself laughing at how ridiculous I feel, but there is a part of me that is equally interested in finding out if this could be a good thing for me. I tend to be a homebody and do not get out much, so there is no way for me to meet people. I scroll through a few profiles before putting my phone down and deciding to go out to get some coffee.

During the car ride, SEAA asks, “Would you like to try a new coffee shop this morning?” I agree to go to the new coffee shop; wondering why SEAA is taking me somewhere I have never been before. When I walk inside the shop, I can smell the scent of freshly brewed coffee, meaning I came at the perfect time to get a cup. Maybe SEAA was right about this place. When I get in line, my phone beeps, and I absently realize the person next to me gets a notification at the same time. I check my phone and see the image of this same stranger along with a message from SEAA’s dating app feature. “Congratulations. Your first match is here! Start a conversation.” I am sure I’m blushing, but I look at the stranger anyway. He gives a similar smile, and after ordering coffee and a pastry, we agree to sit down together and talk. I did not expect the app to work this quickly and without any warning, but I go along with it anyway. Although he seems nice, there is really no spark, and we go our separate ways. I am unsure at this point if I should be trusting SEAA this much. Letting her guide me to places I have never been before to meet strangers that I feel no connection with. What’s the point? “SEAA, I am a little disappointed in this match. What made you think that would be a good idea?” I ask her. “Your interests and careers are similar, and you have a similar schedule and routine as well. Statistically, your relationship would make sense.” I sigh and consider deleting the app from my phone but realize that it will take multiple tries to meet the right person and decide to continue trying. After dating a few different people, I finally settled down in a relationship, but after 6 months of SEAA reassuring me that this was the perfect match, I realized I was not as happy as I could be, and I ended the relationship. Maybe SEAA is not looking for the right things. How much does it matter that a stranger has a similar routine to me? Though, I will continue to use SEAA's features, feeling there is no other option for dating nowadays. Her features remain prevalent in not only this aspect of my life but all aspects. Oddly, before using her dating programming, I never questioned her too much. Work, home, transportation, it didn’t matter. She was a resourceful companion always at my side. But now I am wondering if she is a little too integrated into my life. Food for thought: Would it be weird or cool to have an AI push you out of your comfort zone to meet people? Does the randomness of meetings make it easier or harder to go on dates? Should AI be allowed to make these decisions for you?  Dr. Jacquelyn Schreck, Human Factors Engineer Dr. Jacquelyn Schreck, Human Factors Engineer Catch up with Part 1: Morning Routine, and Part 2: Daytime first! By the time I am done working, it is 6 pm, and I know SEAA is getting dinner ready. Two hours ago, I told SEAA I wanted lasagna, so she ordered groceries, had them delivered, and started making the meal. After prescribing medication to at least 50 patients, I put away my work tablet and turn on a new documentary that SEAA recommended to me. It is about how sea levels had risen by 2 feet, and the entire world finally started working together to combat climate change. Though the sea level will never decrease, we were able to slow down the ice melting rate by 50%. According to this documentary, we were headed toward a world so ridden with pollution we would need oxygen masks just to walk outside. Though I am glad it didn’t come to that, I can’t help but feel the heaviness of the topic continue to weigh on me even after the movie is over. Maybe next time I will ask SEAA specifically for a more lighthearted program that would be better for relaxing. “SEAA, is that burning I smell?” “Yes. The oven malfunctioned, and the temperature was set too high. The issue has been resolved without ruining the food. Dinner will be ready in ten minutes.” When it is dinnertime, I go to the same island counter where I ate my breakfast, and there is a plate of food prepared for me to eat. There is also garlic bread as a side, which I did not ask for, but SEAA thought I would like. She was right, but now I will have to work out for 30 extra minutes later on, and that was not part of my plan this evening.  Image created using Craiyon Image created using Craiyon After eating dinner, I sit down for a few minutes before it is time to work out. I go to my exercise room’s full body mirror and select a guided Pilates workout that is one hour long. This mirror tells me my weight, BMI, body fat percentage, heart rate, and other physiological measures that help me track my fitness. It also guides me on my form and encourages me to keep up the good work, even though sometimes I feel it is not good work and the AI is lying to me to make me feel better. Concluding my workout, I hear running water coming from the bathroom and know my shower has started and should be at my preferred temperature in less than ten seconds. Once I get in, I can tell it is perfectly 103 degrees Fahrenheit, and I enjoy the warmth, allowing it to calm me down as I prepare to settle down for the night. I am not too concerned about wasting water, as this water is collected rainwater and will return to the gray water tank to be cleaned and used again. While in the shower, I brush my teeth and then get out and get in pajamas. As I am getting ready to get into bed, my friend holo calls me, and we talk for a few minutes before hanging up. Now that it is 11 pm, I am ready to climb into bed. The lights started dimming 30 minutes ago, but I asked SEAA to give me an extra 15 minutes since I had a holo call. After climbing into bed, the curtains completely close, and the lights turn all the way off. I spend about 30 minutes scrolling through social media before my eyes start getting droopy, and I fall asleep. Food for thought: Is it creepy or nice that SEAA knew the protagonist would like garlic bread with their meal without them asking? How can we make people care that current practices are ruining the planet? Is it feasible to think the citizens of Earth will one day work together to combat climate change? Don't forget to read part 4: Life Living in a Future Smart City: Dating |

AuthorsThese posts are written or shared by QIC team members. We find this stuff interesting, exciting, and totally awesome! We hope you do too! Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed