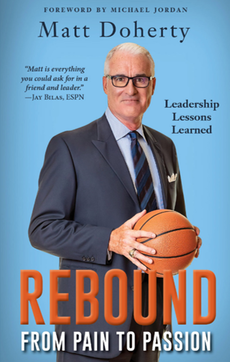

Jennifer Murphy, Ph.D., CEO & Founder Jennifer Murphy, Ph.D., CEO & Founder I recently had the privilege of joining Coach Matt Doherty on his webcast where we talked about a variety of workplace training topics. My first conversation with him was probably one of the most memorable moments of my career to date, as it revolved around two of the things I care most about in the world: leadership and UNC basketball. For those of you who weren't blessed from birth to be a Tar Heel, he played on the 1982 National Championship team alongside Michael Jordan. He's coached at a variety of schools (including my alma mater, Davidson College), but he's best known for his three-year tenure as the head coach of the UNC men's basketball team. After the webcast, Coach sent me a copy of his book Rebound: From Pain to Passion as a token of thanks. I read it cover to cover the next day. In it, he discusses his rise as a coach to one of the most prestigious jobs in the game, the loss of that job, and how he was able to emotionally and professionally recover in the aftermath. He describes the feelings of loss, pain, and betrayal associated with falling off a high pedestal in an extremely public forum. I do not know many people who could recover from something that ego-shattering with grace. Inherent to leadership is learning to be comfortable with people watching and evaluating you. You're on a stage all the time, even on work-from-home Fridays and during happy hour. Even for those of us who like the limelight, it takes a toll. One thing we never talk about is how, as leaders, to manage emotional pain while we're on that stage. It's one thing for a team member to go through a hardship; leaders rally around them, give them the space and support they need, and are patient while life is uncertain. But when it's you? Do you tell your team what's going on, and risk freaking them out? Do you try to model strength in the face of adversity and act like nothing is wrong? Will they think you're making excuses? Will they be scared? Can you handle your whole world knowing that you're not OK?

Basketball teams play a lot of games, which is great for people like me who like to watch them. If you're the coach, that means you have the potential to take a lot of "Ls." In the government contracting space, we do too. I lose a lot more than I win, and that's hard. When you add personal loss on top of that, the cracks start to show. Throw in a pandemic, political tension, and everything else, and honestly, there are some bad days. How do I deal with it? I tend to share in the hopes that the crew will know when it's them, they're in a safe place to ask for help. I also think they have a right to know if I'm not at 100%, and they should understand that this job is hard because one day, it might be theirs. But it's also just as important for them to see me trying to take care of myself, giving myself some grace, and getting better. Is this the right way to handle it? I don't know. But I do know that the world isn't getting any kinder, and this should be a topic we talk about a lot more. Thanks to Coach Doherty for having the courage to write about his experience, and for sharing the lessons he learned from it. You can order Rebound: From Pain to Passion here: https://amzn.to/3Tl8vFV and watch to the Rebound Live Webcast here: https://coachmattdoherty.com/webcast/

0 Comments

|

AuthorsThese posts are written or shared by QIC team members. We find this stuff interesting, exciting, and totally awesome! We hope you do too! Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed