Julian Abich, Ph.D., Senior Human Factors Engineer Julian Abich, Ph.D., Senior Human Factors Engineer I've attended and presented at several conferences this year, such as the Human Systems Digital Experience, World Aviation Training Summit (WATS), and Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics (AHFE), and have noticed a simple yet powerful construct appearing over and over again…self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is "concerned with people’s beliefs in their capabilities to produce given attainments" (Bandura, 2006). In other words, it's the confidence in the ability to exert control over one's own motivation, behavior, and social environment (Carey & Forsyth, 2009). Extensive evidence has shown self-efficacy to be a significant predictor across a variety of contexts and domains, such as college academic performance (Choi, 2005), pre-career pilot performance (Wilson, 2021), weight loss success (Armitage et al., 2014), health management (Arslan, 2012), second language skills (Raoofi, Tan, & Chan, 2012), and work burnout and engagement (Ventura, Salanova, & Lloren, 2015). While there are a host of other areas that have explored the role of self-efficacy, one of particular interest to me that has been gaining more attention is usability. Usability assessments typically focus on effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction, but research suggests the integration of self-efficacy can provide a robust assessment (Martin, 2007). As the preponderance of technological solutions continuously diffuses across all aspects of our personal and work lives, our dependency on them will impact our ability to complete tasks. Therefore, belief in our ability to complete a task with a technological solution should impact the way in which these solutions are designed. Plenty of evidence exists indicating the role of self-efficacy in the adoption of technology, such as mobile learning solutions (Bettayeb, Alshurideh, Al Kurdi, 2020), desktop virtual environments for learning (Makransky & Petersen, 2019), fitness devices (Rupp, Michaelis, McConnel, Smither, 2018), and medical support tools (Lindblom, Gregory, Wilson, Flight, & Zajac, 2012). Although some usability measures focus on or integrate the concept of self-efficacy, not all are implemented correctly based on Bandura's guidance (2006). One major flaw is using Likert-type bipolar ratings (e.g., strongly agree to strongly disagree) instead of unipolar ones (e.g., 0 to 10). The issue is if you have zero confidence in your ability to complete a task, then negative ratings below zero make little sense and lead to skewed interpretations of the results. Further, when bipolar ratings are used, the mid-point (usually labeled as neither agree nor disagree) gets converted into a moderate-level of self-efficacy which is incorrect and not a true reflection of the construct (Bandura, 2012). Leveraging self-efficacy as a usability metric can provide valuable insight into the design and evaluation of technology, but it's critical that measures be developed, implemented, and interpreted appropriately. Bandura (2012) stated that "there is no single all-purpose measure of self-efficacy with a single validity coefficient." This indicates that it's expected for new measures of self-efficacy to be created for, as he puts it, "activity domains." Activity domains are the topic areas in which the tasks under evaluation are performed. For example, evaluating self-efficacy for driving a monster truck. Use these guidelines when developing your measures and scales for usability evaluations (or any evaluation for that matter):

Have you been capturing self-efficacy as part of your usability assessments? Tell us how. References:

Armitage, C. J., Wright, C. L., Parfitt, G., Pegington, M., Donnelly, L. S., & Harvie, M. N. (2014). Self-efficacy for temptations is a better predictor of weight loss than motivation and global self-efficacy: Evidence from two prospective studies among overweight/obese women at high risk of breast cancer. Patient Education and Counseling, 95(2), 254-258. Arslan, A. (2012). Predictive power of the sources of primary school students' self-efficacy beliefs on their self-efficacy beliefs for learning and performance. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 12(3), 1915-1920. Bandura, A. (2006). Guide to the construction of self-efficacy scales. In Pajares, F., Urdan, T. (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents, Vol. 5: 307-337. Greenwich, CT: Information Age. Bandura, A. (2012). On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management, 38(1), 9–44. Bettayeb, H., Alshurideh, M. T., & Al Kurdi, B. (2020). The effectiveness of mobile learning in UAE universities: a systematic review of motivation, self-efficacy, usability and usefulness. Control and Automation, 13(2), 1558-1579. Carey, M.P. & Forsyth, A.D. (2009). Teaching tip sheet: Self-efficacy. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/pi/aids/resources/education/self-efficacy. Choi, N. (2005). Self‐efficacy and self‐concept as predictors of college students' academic performance. Psychology in the Schools, 42(2), 197-205. Lindblom, K., Gregory, T., Wilson, C., Flight, I.H.K., & Zajac, I. (2012). The impact of computer self-efficacy, computer anxiety, and perceived usability and acceptability on the efficacy of a decision support tool for colorectal cancer screening, Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 19(3), 407–412. Makransky, G. & Petersen, G. B. (2019). Investigating the process of learning with desktop virtual reality: A structural equation modeling approach. Computers & Education, 134, 15-30. Martin, C. V. (2007). The Importance of self-efficacy to usability: Grounded theory analysis of a child’s toy assembly task. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 51(14), 865–868. Raoofi, S., Tan, B. H., & Chan, S. H. (2012). Self-Efficacy in Second/Foreign Language Learning Contexts. English Language Teaching, 5(11), 60-73. Rupp, M. A., Michaelis, J. R., McConnell, D. S., & Smither, J. A. (2018). The role of individual differences on perceptions of wearable fitness device trust, usability, and motivational impact. Applied Ergonomics, 70, 77-87. Ventura, M., Salanova, M., & Llorens, S. (2015). Professional self-efficacy as a predictor of burnout and engagement: The role of challenge and hindrance demands. The Journal of Psychology, 149(3), 277-302. Wilson, N. (2021). Pre-Career Pilots and Motivation – What is the Best Predictor of Performance? 23rd World Aviation Training Summit (WATS), Orlando, FL, June 15-16, 2021.

0 Comments

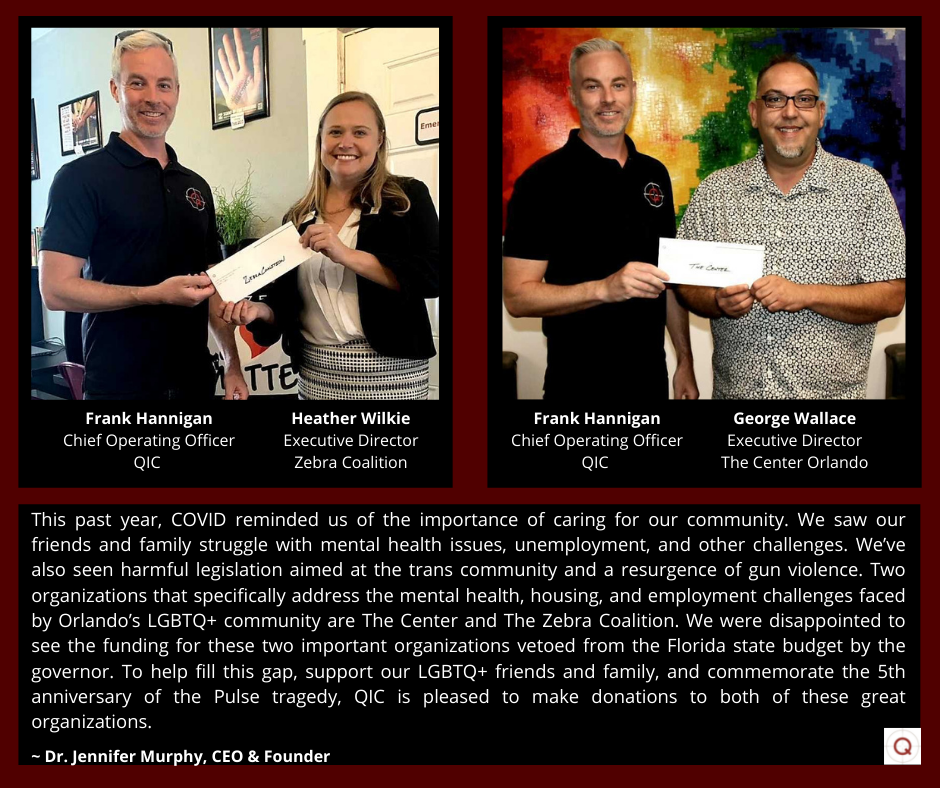

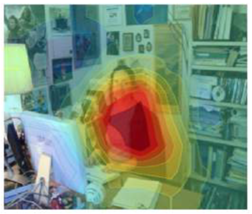

Orlando-based Quantum Improvements Consulting donates $25K to The LGBT+ Center, Zebra Coalition6/8/2021  Grace Teo, Ph.D., Sr. Research Psychologist Grace Teo, Ph.D., Sr. Research Psychologist The major challenge with the use of artificial intelligence (AI) is that it is often difficult to explain how AI or machine learning (ML) solutions and recommendations come to be. Previously this may not matter as much because AI’s use was limited and its recommendations were confined to relatively trivial decisions. In the past few decades, however, AI use has become more pervasive and some of these AI solutions are impacting high-stakes decisions, so this problem has become increasingly important. Fueling the urgency are findings that AI solutions can be unintentionally biased, depending on the type of data used to train the algorithms. For instance, the algorithm used by Amazon to hire staff was found to be biased against women because the algorithm was trained on previous data that largely comprised resumes from male applicants (Shin, 2020). Algorithms used by COMPAS (i.e., Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions) to predict likelihood of recidivism were also found to be predict that black offenders were twice as likely to reoffend compared to white offenders (Shin, 2020). These are only two of many instances of algorithm bias. These algorithms tend to be from “black box” models that are developed from powerful neural networks performing deep learning. These neural networks are usually what researchers have to use for computer vision and image processing which are less amenable to other AI/ML techniques. Researchers in the field of explainable AI (or XAI) have tried to shine a light into these “black boxes” in different ways. For instance, one popular way to help explain deep learning AI processing images is to use heat or saliency maps that show the regions/pixels of a picture that seem to highly influence the algorithm’s prediction (i.e., what the network is “paying attention to”). If these regions aren’t relevant to the algorithm’s task at hand, then the researcher may be looking at a biased algorithm. In her recent talk at a Deep Learning Summit, Rohrbach (2021) showed an example of wrong captioning by a black box model, mislabeling the woman sitting at a desk in front of a computer monitor as “a man” (Figure 1a). The saliency map showed that the network was attending more to the computer monitor than the person in the picture (Figure 1b), when it should have been focusing more on the person (Figure 1c). Presumably the bias arose because the training data contained more images of men sitting in front of computers than women doing the same. Saliency maps also provide a way to evaluate the “logic” of the algorithm even when the captioning seems appropriate (see Figures 2a & 2b). A major criticism of such saliency maps is that they only show the inputs of importance in deriving the algorithm. They do not reveal how these inputs are used. For instance, if two models had different captions or predictions but had very similar saliency maps, the maps would not explain how the models reached their different predictions (Wan, 2020). Due to such limitations, other researchers such as Dr. Cynthia Rudin, propose that instead of making AI explainable, interpretable models should be developed instead. The difference being that interpretable models are inherently understandable, and the researcher is able to see how the model derives its solutions and algorithms, instead of merely trying to coax explanations from a model by reviewing what inputs were more influential than others after the algorithm has been developed (Rudin, 2021). Dr. Rudin’s work to make neural networks interpretable has received wide acclaim and she is a strong proponent of using interpretable models especially for high stakes decisions (Rudin, 2019). However, as she stated in the recent Deep Learning Summit, Dr. Rudin also admitted that developing such interpretable models takes more time and effort. This is because unlike black box models where researchers would not know if the model is working properly, interpretable models force researchers to work to troubleshoot the data when they see that the model is not working as it should – even if the solutions look ok (Rudin, 2021). Nevertheless, there are some who still argue for the use of black box models that are low on explainability. Black box models are harder to copy and can give the company that developed them a competitive advantage. They are also easier to develop. Proponents of this view believe that the goal is not to explain every black box model but to identify when to use black box models (Harris, 2019). If a black box algorithm is able perform its task to a high degree of accuracy, we may not need to know exactly how it did it. Besides, what is a valid explanation to one may not be a valid explanation to another. These researchers argue that even physicians use things that they do not fully understand all the time, to include common drugs that have been shown to be consistently effective even though no one totally comprehends how they work in every patient. What is important is that that enough testing is done to ensure that the algorithm is dependable and suitable for its intended use (Harris, 2019). When I first learned and read about AI and the problem of inexplicability some years back, I remember taking the position that the ends justified the means. That is, so long as the algorithm was accurate I’d be willing to sacrifice explainability. However, as I learn more about how people are using AI solutions for all sorts of important medical, hiring, and criminal justice decisions, I started to reconsider my position. After attending the Deep Learning Summit on Explainable AI (XAI) earlier this year, I am more inclined to think that it really depends on the application and type of decision involved. Just because a black box model has a sterling track record of highly accurate predictions in the past does not mean that it is not possible for the next prediction to be poor. The higher stakes the decision is, the better understanding we should have of the workings of the AI. What do you think? For what applications or decisions would you accept a model that is unexplainable but have been consistently accurate? References

Harris, R. (2019). How can doctors be sure a self-taught computer is making the right diagnosis? Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/04/01/708085617/how-can-doctors-be-sure-a-self-taught-computer-is-making-the-right-diagnosis Rudin, C. (2019). Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nature Machine Intelligence, 1(5), 206-215. Rudin, C. (2021). Stop Explaining Black Box Machine Learning Models for High Stakes Decisions and Use Interpretable Models Instead. Deep Learning Summit 2021. Rohrbach, A. (2021). Explainable AI for addressing bias and improving user trust. Presented at the Deep Learning Summit 2021. Shin, T. (2020). Real-life Examples of Discriminating Artificial Intelligence: Real-life examples of AI algorithms demonstrating bias and prejudice. Retrieved from https://towardsdatascience.com/real-life-examples-of-discriminating-artificial-intelligence-cae395a90070 Wan, A. (2020). What explainable AI fails to explain (and how we fix that). Retrieved from https://towardsdatascience.com/what-explainable-ai-fails-to-explain-and-how-we-fix-that-1e35e37bee07  Michael Schwartz, Human Factors Researcher Michael Schwartz, Human Factors Researcher Preprints first caught my eye in May 2020. As a human factors researcher who has researched wearables for several years and owned a few (remember the Jawbone UP?) my interest was piqued by a Washington Post headline, “Wearable tech can spot coronavirus symptoms before you even realize you’re sick” (Fowler, 2020). The wearable mentioned in the Post article, the Oura ring, must have already been developed before COVID-19 reached the U.S. and a novel application was developed for the existing hardware. Physical and digital prototypes go through iterative design and development processes and while the process can be rushed, speed comes at the expense of quality (e.g., Cyberpunk 2077). Quality is paramount when developing an application for monitoring individual and public health during a pandemic. The initial findings Fowler referenced were reported in preprint form. Preprints are scholarly works posted by researchers before the manuscripts have undergone peer review. Scientific research must be developed over time, much like hardware and software. Studies take months and even years to design, develop, pilot, collect and analyze data, interpret findings, and report the results. Peer review, the process of the scientific community evaluating research for its scientific soundness and practical and applied merit, takes additional months. Preprints are a way for scientists and researchers to put their (unvalidated) findings into the world, thus making sure nobody else can gain credit for the work. No industry standard exists for preprints. Do “initial findings” contain the results of two study participants or 200? Work-in-progress papers have been presented at academic conferences for years. Technical reports are another avenue for quickly reporting research. Why are preprints, which are posted online for the world to consume before peer review has vetted the work, necessary for researchers to make sure no one else receives credit for their work? People may rely on news headlines and information gained through word-of-mouth for health advice. There’s a lot of money to be made. Newspapers need headlines to drive subscriptions, tech startups need investment capital, and researchers need funding. The financial incentives reinforce the people involved until the echo chamber increases sales. The preprint problem is magnified when journalists, who are also looking to not get scooped, take the initial findings and generate headlines that may be contradictory to the final, validated results. What happens if a study that’s initially reported as a preprint is found to be invalid? Is the preprint pulled from the internet? Does the news media issue a retraction? Will future researchers who are looking to develop and test hypotheses be able to distinguish between a preprint and a peer reviewed study? Some article repositories are taking steps to address this issue by clearly labeling which articles are preprints, such as medRxiv (https://www.medrxiv.org/). The following cautionary statement is prominently displayed on medRxiv’s homepage (emphasis medRxiv’s): Caution: Preprints are preliminary reports of work that have not been certified by peer review. They should not be relied on to guide clinical practice or health-related behavior and should not be reported in news media as established information. This is a good first step; however, it is incumbent on journalists and news outlets to responsibly report information. For example, a reporter could state that research into using wearables to aid in early COVID-19 diagnoses is ongoing while also refraining from mentioning any features or capabilities of devices that have not been validated. The results of the first Oura studies are promising. Maybe the Oura ring and similar devices can detect the symptoms of COVID-19 before most people would otherwise spot them, but we don’t know yet. Validation takes time. In the meantime, wash your hands, wear a mask, and physically distance as much as you can. Relying on an unvalidated, non-FDA approved device for disease prevention and detection may lead some people to have a false sense of security when their wearable does not, in fact, indicate they may be ill. This false sense of security could then lead to infecting others. The scientific community can more clearly indicate that preprints are not to be used for individual or organization-level health guidance, as medRxiv has done. Scientists and researchers can choose to not cite preprints in their work, since the issue of what happens when a preprint is invalidated and retracted is still unclear. Companies and institutions can choose to not use preprints as a basis for hiring, promotion, and tenure. The issue of whether researchers should use information reported in preprints as a foundation upon which to scaffold scientific theories needs to be answered. We stand on the shoulders of giants, but without a firm footing we risk regressing down a slippery slope. What are your thoughts on preprints? Let us know, below! References

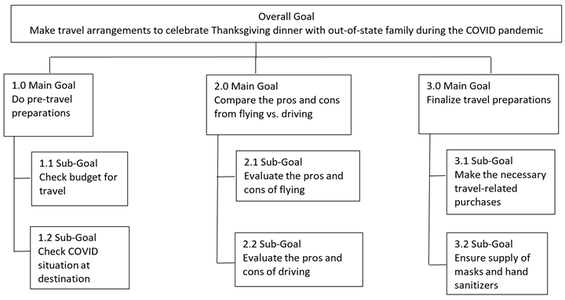

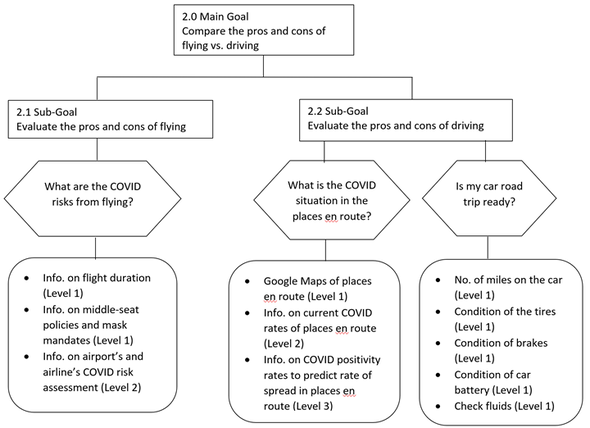

Fowler, G.A. (2020 May 8). Wearable tech can spot coronavirus symptoms before you even realize you’re sick. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/05/28/wearable-coronavirus-detect/  Julian Abich, Ph.D., Senior Human Factors Engineer Julian Abich, Ph.D., Senior Human Factors Engineer This short post was inspired by an article I recently read about a group of dentists that decided to open a practice in NYC (D'Ambrosio, 2020). What's different about it is these dentists offer a very limited number of services (in fact only three: cleaning, whitening, and straightening). No, it's not because they are underqualified to perform other services or they're just lazy, it's because through their research they found most people (i.e., young professionals) in the area don't need the full gamut of services normally offered at the dentist. They also realized most people can't afford to go to the dentist for these basic services because of cost. Now, implementing a "user-centered" business model, these dentists offer clientele the basic services they most often want at a much more affordable price. This is because the overhead costs associated with these three services (i.e., equipment, office space, insurance, etc.) are much lower than a traditional dentist, and those savings are passed on to the clientele. They also completely redesigned their office space with a time-relevant facelift. Their goal is to make going to the dentist similar to going to get a haircut or your nails done…pop in, get a cleaning, and pop out with some money still in your pocket. It's obvious COVID has been a catalyst that has forced businesses to re-evaluate their models and plans over the past year. People have less money to spend, but still have needs to be met. I am by no means a business analyst or have a business degree, but I do understand the importance of focusing on the end-users when designing products, building training programs, or determining a list of services to offer. Many of these topics are partially covered under market research, but by borrowing concepts and approaches from usability, user experience, neuroscience, and other related fields, businesses can gather different types of research data to better inform their decisions. For example, restaurants, wineries, and supermarkets have used behavioral science (e.g., eye-tracking data) to inform menu redesigns or product options, resulting in better customer experiences and bottom lines (e.g. Cobe, 2020; Huseynov, Kassas, Segovia & Palma, 2019; Wästlund, Shams, & Otterbring, 2018). It shows that a bit of research to understand customer needs and creative thinking based on the data can go a long way. Two takeaways: 1) Understand user needs regardless of your business focus and design to meet those needs. 2) Look to other sources of data not traditionally used to inform these related business decisions as a way to better understand your users and clientele. This can lead to better user experiences and improve overall customer satisfaction. How are you seeking to understand your customer needs and how is data informing your "user centered" business decisions? Let us know what challenges you're facing and we'll let you know how we can help. Reference: Cobe, P. (2020, September 25). Texas restaurants turn to neuroscience for menu makeovers. Restaurant Business. https://www.restaurantbusinessonline.com/technology/texas-restaurants-turn-neurosciencemenu-makeovers D'Ambrosio, D. (2020, January 18). Take a trip to Beam Street for a new kind of dentist. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/danieldambrosio/2020/01/18/take-a-trip-to-beam-street-for-a-new-kind-of-dentist/?sh=792aaf52bf77 Huseynov, S., Kassas, B., Segovia, M.S., & Palma, M.A. (2019). Incorporating biometric data in models of consumer choice. Applied Economics, 51(14), 1514-1531. Wästlund, Shams, & Otterbring, (2018). Unsold is unseen … or is it? Examining the role of peripheral vision in the consumer choice process using eye-tracking methodology. Appetite, 120, 49-56.  Grace Teo, Ph.D., Sr. Research Psychologist Grace Teo, Ph.D., Sr. Research Psychologist Like almost everything else, Thanksgiving this year will be far from normal thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic. No doubt most of us are still keen to carry on with the activities that characterize the season. My goal this Thanksgiving is modest: to have a safe, enjoyable, delicious, Thanksgiving where I get to catch up with family and friends, recounting fond memories, dodging embarrassing questions, enduring rude remarks and avoiding arguments. Yes, a good Thanksgiving. COVID has definitely added concerns to my travel plans, as it has with others (Sarmiento & Wamsley, 2020). Should I fly or drive? What are the COVID risks from being at the airport? Is it enough that the airline mandates masks to be worn at all times? What should be my route if I’m driving and what are the COVID risks from that? Leading a QIC project that is employing Goal Directed Task Analysis (GDTA; Endsley, Bolte, & Jones, 2003), I decided to apply it in the context of my travel conundrum. A GDTA documents a task in terms of the goals to be achieved, the key decisions that determine the extent which the goals are met, and the information requirements needed to make those decisions. The GDTA has been used to describe complex unstructured tasks that can involve ill-defined processes and outcomes such as maritime navigation (Sharma, 2019), critical monitoring tasks (Rummukainen, 2016), paramedics’ tasks (Abd Hamid & Waterson, 2010), supervisory control tasks (Kaber et al., 2006), and command and control decision making (Bolstad et al., 2000), so of course it is capable of helping to resolve my problem. Applying the GDTA methodology to my overall goal is to make travel arrangements for Thanksgiving this year, I defined the main and subgoals in the following Goal Hierarchy (Endsley, 1993) (see Figure 1). According to Endsley and Garland (2000), the GDTA information required can be further categorized as that which enables the decision maker to:

After identifying the above goals and subgoals, I identified the decisions that are associated with these goals as well as the information I needed to make those decisions at various levels. The result is a Relational Hierarchy (Figure 2). So, have I made my decision yet? Well, no… but thanks to the GDTA process I have systematically determined the information needed to make that decision. As new information becomes available, I can apply it to this framework. If another viable transportation mode is suddenly invented (e.g. teleportation), I can expand the analysis to include that mode of transportation. Has the COVID pandemic changed the way you are making your travel plans this Thanksgiving? Try doing your own GDTA to see if that helps. [Addition 09/15/2021] - there is also a wealth of information available specifically for seniors. much of which is also applicable to the general public here - https://www.bankrate.com/insurance/car/senior-driver-safety-amid-covid/. References

Abd Hamid, H., and Waterson, P. (2010). Using Goal Directed Task Analysis to Identify Situation Awareness Requirements of Advanced Paramedics. Int. Conf. Adv. Hum. Factors Ergon. Healthcare, 672-680. Bolstad, C. A., Riley, J. M., Jones, D. G., & Endsley, M. R. (2002). Using goal directed task analysis with Army brigade officer teams. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting (Vol. 46, No. 3, pp. 472-476). Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications. Endsley, M. R. and Garland D. J (Eds.) (2000) Situation Awareness Analysis and Measurement. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Endsley, M.R., Bolte, B., & Jones, D.G. (2003), Designing for Situation Awareness: An Approach to Human-Centred Design. Taylor & Francis: London. Kaber, D. B., Segall, N., Green, R. S., Entzian, K., & Junginger, S. (2006). Using multiple cognitive task analysis methods for supervisory control interface design in high-throughput biological screening processes. Cognition, technology & work, 8(4), 237-252. Rummukainen, L., Oksama, L., Timonen, J., & Vankka, J. (2015). Situation awareness requirements for a critical infrastructure monitoring operator. In 2015 IEEE International Symposium on Technologies for Homeland Security (HST) (pp. 1-6). IEEE. Sarmiento, I.G. & Wamsley, L. (2020). Coronavirus FAQs: Is It Safer To Fly Or Drive? Is Air Conditioning A Threat? Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/05/30/865340134/coronavirus-faqs-is-it-safer-to-fly-or-drive-is-air-conditioning-a-threat Sharma, A., Nazir, S., & Ernstsen, J. (2019). Situation awareness information requirements for maritime navigation: A goal directed task analysis. Safety Science, 120, 745-752.  Michael King, Ph.D., Human Factors Researcher Michael King, Ph.D., Human Factors Researcher At its core, coaching is a form of individual and team development in which the coach helps to bring out the potential of the learner. The coach does this in a manner which supports, encourages, and most importantly, places responsibility for development with the learner (Dembkowski, 2006). There are four core qualities that make up every effective coach, no matter the style by which they lead. 1. Building Rapport and Relationships Rapport is the presence of a close and trusting relationship in which the learner and the coach understand each other’s ideas and communicate well. Rapport building involves getting to know one another, understanding where each other come from and what their background is, and most importantly spending time with one another. 2. Asking Questions and Listening Where are you now, and where do you want to go? Helping learners gain insight through self-evaluation is a key part to coaching. Good coaches listen carefully, are open to learners’ perspectives, and allow learners to vent thoughts and emotions without judgement. 3. Providing Effective Feedback Coaches that provide effective feedback focus on facts and observed actions, rather than personal reflections of what they think about the learner or team (Dembkowski, 2006). Feedback should be honest, but not judgmental. Good coaches recognize that an important part of their role is to challenge the learner, and giving feedback is a good way to deliver this. 4. Setting Goals and Delivering Results Effective coaching is about achieving goals. The coach helps the learner set meaningful targets and identify specific behaviors for meeting them. The coach helps to clarify milestones or measures of success and holds the learner accountable for them (Forbes, 2010). Goals are much more likely to be accomplished if they are specific, and clearly defined (Dembkowski, 2006). A Tale of Two Coaches Bobby Knight, nicknamed “The General”, was the head men’s basketball coach for the Indiana Hoosiers from 1971-2000, and for Texas Tech from 2001-2008. While at Indiana, Knight let his teams to three NCAA championships and 11 Big Ten Conference championships. He also coached the 1984 USA men’s Olympic team to a gold medal, and has the third most wins in NCAA coaching history. Though we was highly successful, innovative coach, Knight is probably best known for his short temper, angry outbursts, and for throwing a chair across the floor during one of his more famous tirades. Phil Jackson, nicknamed the “The Zen Master”, was the head basketball coach for the Chicago Bulls from 1987-1998, and for the Los Angeles Lakers from 1999-2004 (and again from 2005-2011). Phil Jackson coached his teams to eleven (11!) NBA championships, an NBA record. Jackson studied human psychology, native American philosophy, and Zen meditation to help him inform coaching strategies. He taught players mindfulness, selflessness, and would lead breathing exercises while burning sage in the locker room. Technology and Coaching

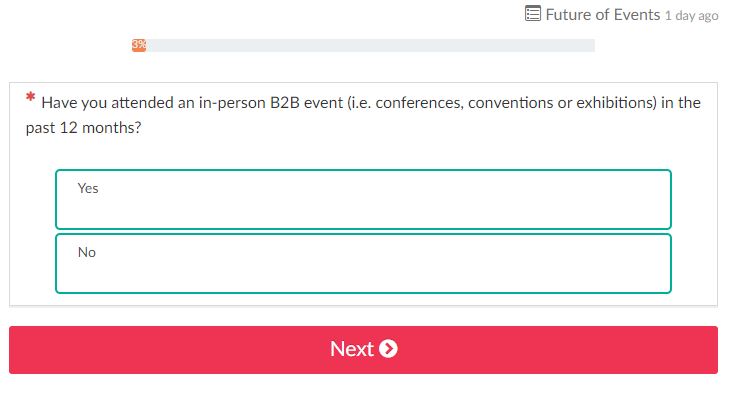

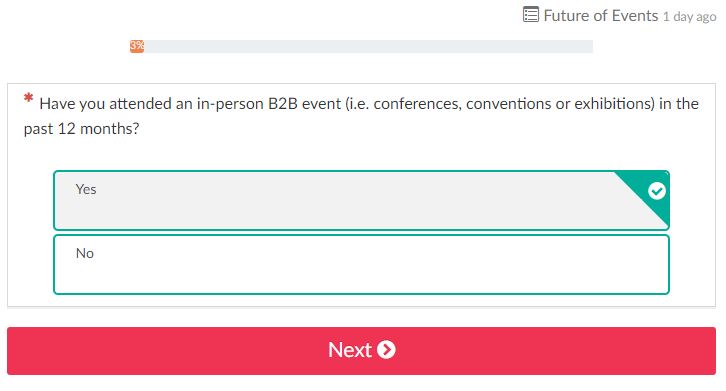

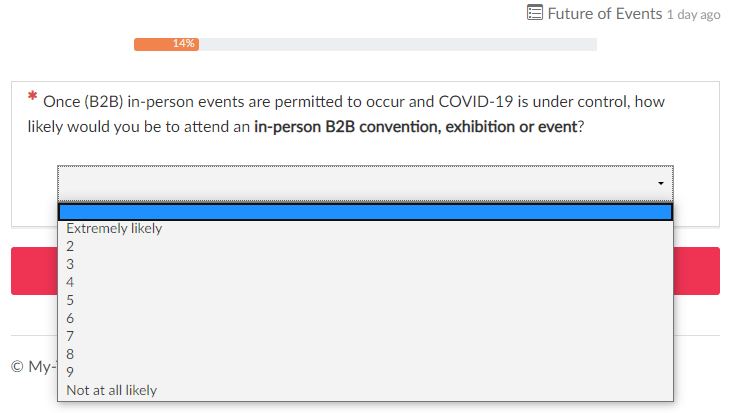

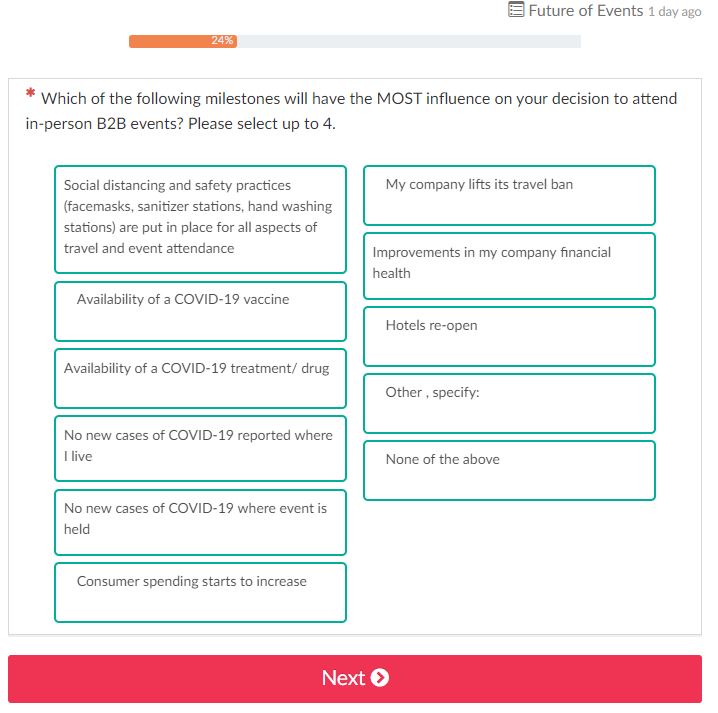

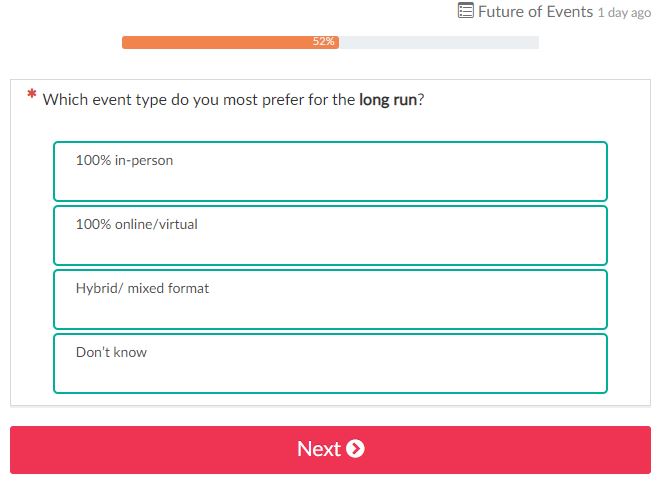

The importance of coaching is evident, regardless of the style of coaching. However, finding a coach is not exactly an easy task. Until recently, the idea of going to the store and buying a coach for an activity that you are trying to improve on or become an expert in, would have seemed ridiculous. Technology has changed this. There is an endless number of apps on Google Play and Apple’s App Store that boast unique automated coaching experiences. Some of these apps can provide this unique coaching experience through artificial intelligence (AI), which is allowing for a more individualized coaching experience without human intervention. But, how can technology accomplish the four core qualities discussed earlier? Is it possible for AI to achieve features such as rapport building, and asking questions and listening? Even more complex, how does it account for different styles of coaching, that get results in different situations? How does it account for the General vs. Zen Master problem. A big part of this challenge is analyzing behavior based on understanding the learner and the performance environment. In my next installment, I will talk about how technology, and specifically AI, is beginning to overcome this challenge. What are your thoughts? References Dembkowski, S. (2006). The seven steps of effective coaching. Thorogood Publishing. Frankovelgia, C. (2013, June 19). The key to effective coaching. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/2010/04/28/coaching-talent-development-leadership-managing-ccl.html  Shabnam Mitchell, PMP, PMI-ACP Shabnam Mitchell, PMP, PMI-ACP Shabnam Mitchell is QIC's new Project Manager! An Agile Certified Practitioner, she has 9 years of experience applying Agile methodologies and frameworks to promote organization efficiency and success. Her experience comes from a wide range of exposures from the banking and financial industries to education and construction managing both large scale and highly critical projects. Shabnam holds an MBA from the University of Phoenix and a B.A. in Economics and Urban Studies from the University of Texas at Austin. Shabnam has led projects from corporate business continuity initiatives and small business change management projects to program and portfolio management through digital disruptions. Shabnam’s professional interests are rooted in simplifying challenging endeavors while engaging and enabling teams to take risks and do their best work, whether in the classroom, at the jobsite, or in the office.  Julian Abich, Ph.D., Senior Human Factors Engineer Julian Abich, Ph.D., Senior Human Factors Engineer I'll start this out like every blog post in 2020…COVID-19 sucks and has thrown a wrench into everything! From a professional perspective, it has affected us all in different ways, but overall it has forced us to rethink the way we conduct our work. As human factors|UX/UI researchers, this has greatly limited our ability to conduct live field research with human participants. Because of this, methodologies to collect data right now are focused heavily on online or remote approaches. Specifically, web-based surveys may be flooding your inbox. The general use of surveys have been around for quite some time, at a minimum of over a century within the U.S. (Converse, 1987). Web-based methods have been in use since the early days of the internet. Some state it was one of the most significant advances in survey technology within the 20th century (Dillman, 2000). "With great power comes great responsibility" (I'll attribute this quote to the late and great Stan Lee). Okay, so survey writing may not be a superpower, but it is a powerful tool for collecting quantitative and qualitative data when implemented correctly. Actually, if I can understand a person's behavioral patterns based on collected data, then that kind of gives me the power to predict the future. I guess I do have superpowers!  Despite the longevity and broad applications of surveys, I constantly come across poorly designed online surveys and it hurts my human factors brain. This is likely because anyone can create a survey if they want, especially web-based, but this doesn't mean you should. So what should you do? Work with professionals who are trained to extract valuable information from participants or respondents. It may seem like an easy task to do on your own, but being able to generate a valid and effective survey is as much of an art as it is a science. You don't become a great scientist or artist overnight, it takes time and experience to hone those skills.  Think about it this way, if you're planning to use the data collected from a survey to drive decisions about a product design, an event, or whatever, don't you think it's important to gather the most informative data possible? Especially if these products or events cost hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars to develop. I'll answer for you…YES! So why are there still so many issues with online surveys? I say it's probably because people don't know what they don't know. They aren't aware or trained how to create appropriately worded questions, or organize the flow, or understand the factors that might influence a person's response to a question. And therefore, they end up drawing conclusions that don't accurately reflect respondents' views, behaviors, or beliefs. The end result may be a poorly designed product that no one wants to use. As I am writing this I received another request to fill out a survey. This one is to get feedback on future audiovisual events and gain insight on future needs to help produce in-person and virtual events. Let's see how well this survey is designed or if there are ways it can be improved. Target the right audience. The email was sent to me because I attended a related conference last year. So far so good. Randomly sampling the population is another way to collect survey data and is what makes web-based surveys so attractive, but sampling techniques should be dependent on the context of the survey. Always spell out acronyms. Not all respondents are going to know what the acronyms are so it's best to make sure they are always spelled out, at least the first time they are used. Below is an example of the first question that is asked. Besides the question, do you notice any other potential issues with the format or design of the form? (Don't ask me what "Future of Events 1 day ago" means because I have no idea) This is what the form looks like when you choose an answer. See any other issues with how it's designed? Maybe a color selection issue? Rating scales should align with the questions and be consistent. First, the scale should make sense when associated with a question. When Likert-type scales are used to gather responses, the lower end of the scale usually refers to less agreement, frequency, importance, likelihood, or quality. Do you see an issue with the scale below? Second, anchor labels could be used to show the extreme ends of the scale, but should still have an associated value (although it's best to have labels and values for every level of the scale to avoid confusion). Third, a label for the center of the scale should be provided because the middle may be assumed to be a neutral response. Fourth, the scales should be consistent as much as possible throughout the survey. Meaning, if you're using a 10-point scale, the don't make the next question a five- or seven-point as seen in the images below. This just makes answering questions more challenging for the respondents. Avoid double barreled questions. The questions above are also designed poorly because there are multiple items in the questions that the respondents might not agree with. Asking the respondents if they prefer "workshops, panels, and training" to be online is taking away the ability for respondents to agree with one of those only. It may seem tedious, but these types of questions need to be reworded or broken out into separate questions. Avoid leading and loaded questions. Do not force respondents to provide answers that don't truly reflect their sentiment. Below it asks respondents to select up to four, but what if respondents only agreed with one or two items? Now you're forcing respondents to provide biased answers that don't truly reflect how they feel or would behave. See a problem with this? Rephrasing the question to say they could choose up to four is different than saying they have to choose them. Make sure the question wording is clear and well defined. Don't leave the wording of questions open for interpretation (unless that is intentional). Every included word should be chosen with a clear purpose. If you asked different respondents what "long run" meant, you would probably receive many different answers. These are just some examples to highlight the challenges with creating a valid survey, although there are many other issues that can arise. It may not be obvious until you sit down to analyze the data that you have a complex data set and it's difficult (or impossible) to generate appropriate conclusions for decision-making. Don't waste your time and resources collecting worthless data when you can do it correctly the first time. You'll be happy, your boss will be happy, your customers will be happy, and the respondents will be happy to know their opinions matter. Contact us if you have any questions (no pun intended) or need support with your data collection efforts. References:

Converse, J. M. (1987). Survey research in the United States: Roots and emergence, 1890–1960. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Dillman, D. A. (2000). Mail and Internet surveys--The tailored design method. New York : John Wiley & Sons, Inc. |

AuthorsThese posts are written or shared by QIC team members. We find this stuff interesting, exciting, and totally awesome! We hope you do too! Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed